Steve Fossett

| Steve Fossett | |

|---|---|

Fossett stands next to GlobalFlyer in 2006 |

|

| Born | James Stephen Fossett April 22, 1944 Jackson, Tennessee |

| Died | c. September 3, 2007 (aged 63) Sierra Nevada Mountains, California |

| Cause of death | Plane crash |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Washington University in St. Louis Stanford University |

| Known for | Business, aviation, sailing, and adventuring |

James Stephen Fossett (April 22, 1944 – c. September 3, 2007) was an American businessman, aviator, sailor, and adventurer and the first person to fly solo nonstop around the world in a balloon. He made his fortune in the financial services industry, and was best known for many world records, including five nonstop circumnavigations of the Earth: as a long-distance solo balloonist, as a sailor, and as a solo flight fixed-wing aircraft pilot.

A fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and the Explorers Club, Fossett set 116 records in five different sports, 60 of which still stood as of June 2007[update].[1]

On September 3, 2007, Fossett was reported missing after the plane he was flying over the Nevada desert failed to return.[2] Despite a month of searches by the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) and others, Fossett could not be found, and the search by CAP was called off on October 2, 2007. Privately funded and privately directed search efforts continued, but after a request from Fossett's wife, he was declared legally dead on February 15, 2008.

On September 29, 2008, a hiker found Fossett's identification cards in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, and the crash site was discovered a few days later (on 1 October 2008) 90 miles (140 km) from where he took-off, although his remains were not initially found. On November 3, 2008, tests conducted on two bones recovered about 750 feet from the site of the crash produced a match to Fossett's DNA.

Contents

|

Early years

Fossett was born in Jackson, Tennessee but he grew up in Garden Grove, California.[1]

Fossett's interest in adventure began early. As a Boy Scout, he grew up climbing the mountains of California, beginning with the San Jacinto Mountains.[3] "When I was 12 years old I climbed my first mountain, and I just kept going, taking on more diverse and grander projects."[4] Fossett said that he did not have a natural gift for athletics or team sports, so he focused on activities that required persistence and endurance.[5] His father, an Eagle Scout, encouraged Fossett to pursue these types of adventures and encouraged him to become involved with the Boy Scouts early.[3] He became an active member of Troop 170 in Orange, California. At age 13,[3] Fossett earned the Boy Scouts' highest rank of Eagle Scout[6] and was a Vigil Honor member of the Order of the Arrow, the Boy Scouts' honor society, where he served as lodge chief.[6] He also worked as a Ranger at Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico during the summer of 1961.[7] Fossett said in 2006 that Scouting was the most important activity of his youth.[3]

In college at Stanford University, Fossett was already known as an adventurer; his Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity brothers convinced him to swim to Alcatraz and raise a banner that read "Beat Cal" on the wall of the prison, closed two years previously. (He made the swim, but was thwarted by a security guard when he arrived.)[5] While at Stanford, Fossett was a student body officer, and he served as the president of a few clubs.[3] In 1966, Fossett graduated from Stanford with a degree in economics.[8] Fossett spent the following summer in Europe climbing mountains and swimming the Dardanelles.[5]

Business career

In 1968, Fossett received an MBA from the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, where he was later a longtime member of the Board of Trustees.[9] Fossett's first job out of business school was with IBM; he then served as a consultant for Deloitte and Touche, and later accepted a job with Marshall Field's. Fossett later said, "For the first five years of my business career, I was distracted by being in computer systems, and then I became interested in financial markets. That's where I thrived."[3]

Fossett then became a successful commodities salesman in Chicago, first for Merrill Lynch in 1973, where he proved a highly successful producer of commission revenue for himself and that firm. He began working in 1976 for Drexel Burnham, which assigned him one of its memberships on the Chicago Board of Trade and permitted him to market the services of the firm from a phone on the floor of that exchange. In 1980, Fossett began the process that eventually produced his enduring prosperity: renting exchange memberships to would-be floor traders, first on the Chicago Board Options Exchange.[5][10]

After 15 years of working for other companies,[3] Fossett founded his own firms, Marathon Securities and Lakota Trading, from which he made millions renting exchange memberships.[1][8][11] He founded Lakota Trading for that purpose in 1980.[12] In the early 1980s,[3] he founded Marathon Securities and extended that successful formula to memberships on the New York stock exchanges. He earned millions renting floor trading privileges (exchange memberships) to hopeful new floor traders, who would also pay clearing fees to Fossett's clearing firms in proportion to the trading activity of those renting the memberships. In 1997, the trading volume of its rented memberships was larger than any other clearing firm on the Chicago exchange.[5] Lakota Trading replicated that same business plan on many exchanges in the United States and also in London.[3] Fossett would later use those revenues to finance his adventures.[1][8][11] Fossett said, "As a floor trader, I was very aggressive and worked hard. Those same traits help me in adventure sports."[5]

Fossett said he did not participate in any of the "interesting things" he had done in college during his time in exchange-related activities: "There was a period of time where I wasn't doing anything except working for a living. I became very frustrated with that and finally made up my mind to start getting back into things."[3] He began to take six weeks a year off to spend time on sports and eventually moved to Beaver Creek, Colorado, in 1990, where for a time he ran his business from a distance.[3] Fossett later sold most of his business interests,[1][13] although he maintained an office in Chicago until 2006.[3]

Personal life

Fossett was married to Peggy Fossett (Viehland), originally from Richmond Heights, Missouri, in 1968.[9] They had no children.[12][14] The Fossetts had homes in Beaver Creek, Colorado, and Chicago and a vacation home in Carmel, California.[5][9][13]

Fossett became well-known in the United Kingdom for his friendship with billionaire Richard Branson, who financed some of Fossett's adventures.[1]

Records

Overview

Steve Fossett was well known for his world records and adventures in balloons, sailboats, gliders, and powered aircraft. He was an aviator of exceptional breadth of experience, from his quest to become the first person to achieve a solo balloon flight around the world (finally succeeding on his sixth attempt, in 2002) to setting, with co-pilot Terry Delore, 10 of the 21 Glider Open records, including the first 2,000 km Out-and-Return, the first 1,500 km Triangle and the longest Straight Distance flights. His achievements as a jet pilot in a Cessna Citation X include records for U.S. Transcontinental, Australia Transcontinental, and Round-the-World westbound non-supersonic flights.[15] Prior to Fossett's aviation records, no pilot had held world records in more than one class of aircraft; Fossett held them in four classes.[3]

In 2005, Fossett made the first solo nonstop and unrefueled circumnavigation of the world in 67 hours in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, a single-engine jet aircraft.

In 2006, he again circumnavigated the globe nonstop and unrefueled in 76 hours, 45 minutes in the GlobalFlyer, setting the record for the longest flight by any aircraft in history with a distance of 25,766 statute miles (41,467 km).[1]

He set 91 aviation world records ratified by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale , of which 36 stand,[16] plus 23 sailing world records ratified by the World Sailing Speed Record Council.

On August 29, 2006 he set the world altitude record for gliders over El Calafate, Argentina at 50,722 feet (15,460 m).

Balloon pilot

On February 21, 1995, Fossett landed in Leader, Saskatchewan, Canada, after taking off from South Korea, becoming the first person to make a solo flight across the Pacific Ocean in a balloon.[17]

In 2002, he became the first person to fly around the world alone, nonstop, in a balloon. He launched the 10-story high balloon Spirit of Freedom from Northam, Western Australia, on June 19, 2002 and returned to Australia on July 3, 2002, subsequently landing in Queensland, Australia. Duration and distance of this solo balloon flight was 13 days, 8 hours, 33 minutes (14 days 19 hours 50 minutes to landing), 20,626.48 statute miles (33,195.10 km).[17] The balloon dragged him along the ground for 20 minutes at the end of the flight. The control center for the mission was in Brookings Hall at Washington University in St. Louis.[18] Fossett's top speed during the flight was 186 miles per hour (299 km/h) over the Indian Ocean. Only the capsule survived the landing; it was taken to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, where it was displayed.[19] The trip set a number of records for ballooning: Fastest (200 miles per hour (320 km/h), breaking his own previous record of 166 miles per hour (270 km/h)), Fastest Around the World (13.5 days), Longest Distance Flown Solo in a Balloon (20,482.26 miles (32,963.00 km)20,482.26 miles), and 24-Hour Balloon Distance (3,186.80 miles (5,128.66 km) on July 1).[20]

While Fossett had financed five previous tries himself, his successful record-setting flight was sponsored by Bud Light.[19] In the end, Fossett actually made money on all his balloon flights; he bought a contingency insurance policy for $500,000 that would pay him $3 million if he succeeded in the flight, and along with sponsorship, that payout meant that in the end, Fossett did not have to spend any of his money other than for initial expenses.[3]

Sailor

Fossett was one of the world's most accomplished sailors. Speed sailing was his speciality and from 1993 to 2004 he dominated the record sheets, setting 23 official world records and nine distance race records. He is recognized by the World Sailing Speed Record Council as "the world's most accomplished speed sailor."[1]

On the maxi-catamaran Cheyenne (formerly named PlayStation), Fossett twice set the prestigious 24 Hour Record of Sailing. In October 2001, Fossett and his crew set a transatlantic record of 4 days 17 hours, shattering the previous record by 43 hours 35 minutes — an increase in average speed of nearly seven knots.

In early 2004, Fossett, as skipper, set the world record for fastest circumnavigation of the world (58 days, 9 hours) in Cheyenne with a crew of 13. In 2007, Fossett held the world record for crossing the Pacific Ocean in his 125-foot (38 m) sailboat, the PlayStation, which he accomplished on his fourth try.[5][13]

Airship pilot

Fossett set the Absolute World Speed Record for airships on October 27, 2004. The new record for fastest flight was accomplished with a Zeppelin NT, at a recorded average speed of 62.2 knots (115.0 km/h, 71.5 mph). The previous record was 50.1 knots (92.8 km/h, 57.7 mph) set in 2001 in a Virgin airship. In 2006, Fossett was one of only 17 pilots in the world licensed to fly the Zeppelin.[3]

Fixed-wing aircraft pilot

GlobalFlyer

Fossett made the first solo nonstop fixed-wing aircraft flight around the world between February 28, 2005, and March 3, 2005. He took off from Salina, Kansas, where he was assisted by faculty members and students from Kansas State University, and flew eastbound, with the prevailing winds, returning to Salina after 67 hours, 1 minute, 10 seconds, without refueling or making intermediate landings. His average speed of 342.2 mph (550.7 km/h) was also the absolute world record for "speed around the world, nonstop and non-refueled." His aircraft, the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, had a carbon fiber reinforced plastic airframe, with a single Williams FJ44 turbofan engine. It was designed and built by Burt Rutan and his company, Scaled Composites, for long-distance solo flight. The fuel fraction, the weight of the fuel divided by the weight of the aircraft at take-off, was 83 percent.[21][22][23]

On February 11, 2006, Fossett set the absolute world record for "distance without landing" by flying from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida, around the world eastbound, then upon returning to Florida continuing across the Atlantic a second time to land in Bournemouth, England. The official distance was 25,766 statute miles (41,467 km) and the duration was 76 hours 45 minutes.

The next month, Fossett made a third flight around the world in order to break the absolute record for "Distance over a closed circuit without landing" (with takeoff and landing at the same airport). He took off from Salina, Kansas on March 14, 2006 and returned on March 17, 2006 after flying 25,262 statute miles (40,655 km).

There are only seven absolute world records for fixed-wing aircraft recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and Fossett broke three of them in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer.[24] All three records were previously held by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager from their flight in the Voyager in 1986. Fossett contributed the GlobalFlyer to the Smithsonian Institution’s permanent collection.[25] It is on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum.[26] Fossett flew the plane to the Center and taxied the plane to the front door.[27]

Transcontinental aircraft records

Fossett set two U.S. transcontinental fixed-wing aircraft records in the same day. On February 5, 2003, he flew his Cessna Citation X jet from San Diego, California to Charleston, South Carolina in 2 hours, 56 minutes, 20 seconds, at an average speed of 726.83 mph (1169.73 km/h) to smash the transcontinental record for non-supersonic jets.

He returned to San Diego, then flew the same course as co-pilot for fellow adventurer Joe Ritchie in Ritchie's turboprop Piaggio Avanti. Their time was 3 hours, 51 minutes, 52 seconds, an average speed of 546.44 mph (879.46 km/h), which broke the previous turboprop transcontinental record held by Chuck Yeager and Renald Davenport.

Fossett also set the east-to-west transcontinental record for non-supersonic fixed-wing aircraft on September 17, 2000. He flew from Jacksonville, Florida to San Diego, California in 3 hours, 29 minutes, at an average speed of 591.96 mph (952.67 km/h).

First trans-Atlantic flight re-enactment

On July 2, 2005, Fossett and co-pilot Mark Rebholz re-created the first nonstop crossing of the Atlantic which was made by the British team of John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown in June 1919 in a Vickers Vimy biplane. Their flight from St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada to Clifden, Ireland in the open cockpit Vickers Vimy replica took 18 hours 25 minutes with 13 hours flown in instrument flight conditions. Because there was no airport in Clifden, Fossett and Rebholz landed on the 8th fairway of the Connemarra Golf Course.[3]

Glider records

The team of Steve Fossett and Terry Delore (NZL) set ten official world records in gliders while flying in three major locations: New Zealand, Argentina and Nevada, United States. An asterisk (*) indicates records subsequently broken by other pilots.

- Distance (Free) World Record 2,192.9 km, December 4, 2004.[28]

- Triangle Distance (Free) World Record* 1,509.7 km, December 13, 2003.[29]

- Out and Return Distance (Free) World Record* 2,002.44 km, November 14, 2003.[30]

- 1,500 Kilometer Triangle World Record 119.11 km/h (74.02 mph), December 13, 2003.[31]

- 1,250 Kilometer Triangle U.S. National Record 143.48 km/h (89.51 mph). Exceeded world record by 0.01 km/h, July 30, 2003.[32]

- 750 Kilometer Triangle World Record* 171.29 km/h (106.44 mph), July 29, 2003.[33]

- 500 Kilometer Triangle World Record* 187.12 km/h (116.27 mph), November 15, 2003.[34]

- 1,000 km Out-and-Return World Record* 166.46 km/h (103.44 mph), December 12, 2002.[35]

- 1,500 km Out-and-Return World Record* 156.61 km/h (97.30 mph), November 14, 2003.[36]

- Triangle Distance (Declared) World Record* 1,502.6 km, December 13, 2003.

- Out-and-Return Distance (Declared) World Record* 1,804.7 km, November 14, 2003.

Fossett and co-pilot Einar Enevoldson flew a glider into the stratosphere on August 29, 2006. The flight set the Absolute Altitude Record for gliders at 50,727 feet (15,460 m).[37] Since the glider cockpit was unpressurized, the pilots wore full pressure suits (similar to space suits) so that they would be able to fly to altitudes above 45,000 feet (14,000 m). Fossett and Enevoldson had made previous attempts in three countries over a period of five years before finally succeeding with this record flight. This endeavor is known as the Perlan Project.

Cross-country skiing

As a young adventurer, Fossett was one of the first participants in the Worldloppet, a series of cross country ski marathons around the world. While he had little experience as a skier, he was in the first group of 'citizen athletes' to participate in the series debut in 1979. And in 1980, he became the eighth skier to complete all 10 of the long distance races, earning a Worldloppet medallion. He has also set cross-country skiing records in Colorado, setting an Aspen to Vail record of 59 hr, 53 min, 30 sec in February 1998, and an Aspen to Eagle record of 12 hr, 29 min in February 2001.[3]

Mountain climbing

Fossett was a lifelong mountain climber and had climbed the highest peaks on six of the seven continents.[5][11] In the 1980s, he became friends with Patrick Morrow, who was attempting to climb the highest peaks on all seven continents for the "Seven Summits" world record (which Morrow did achieve in 1985). Fossett accompanied Morrow for his last three peaks, including Vinson Massif in Antarctica, Carstensz Pyramid in Oceania, and Elbrus in Europe.[3] While Fossett went on to climb almost all of the Seven Summits peaks himself, he declined to climb Mount Everest in 1992 due to asthma.[3] He also later returned to Antarctica to climb again.

Other accomplishments

Fossett competed in and completed premier endurance sports events, including the 1,165-mile (1,875 km) Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, in which he finished 47th on his second try in 1992 after training for five years. He became the 270th person to swim across the English Channel on his fourth try in September 1985 with a time of 22 hours, 15 minutes.[3][5][17] Although Fossett said he was not a good enough swimmer "to make the varsity swim team", he found that he could swim for long periods.[3] Fossett has run in the Ironman Triathlon in Hawaii[9] (finishing in 1996 in 15:53:10),[38] the Boston Marathon, and the Leadville Trail 100, a 100-mile (160 km) Colorado ultramarathon which involves running up elevations of more than 14,000 feet (4,300 m) in the Rocky Mountains.[5][8]

Fossett had raced cars in the mid-1970s and later returned to the sport in the 1990s.[3] He competed in the 24 hours of Le Mans road race twice, in 1993 and in 1996,[10][11] along with the Paris to Dakar Rally.[5]

Previous attempts at records

Fossett tried six times over seven years for the first solo balloon circumnavigation. His fifth attempt cost him $1.25 million of his own money; his sixth and successful attempt was commercially sponsored.[3] Two of the attempts were launched from Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, and Washington University in St. Louis served as control center for four of the six flights, including the record-breaking one.[9]

In 1998, one of the unsuccessful attempts at the ballooning record ended with a five-mile (8 km) plummet into the Coral Sea off the coast of Australia that nearly killed Fossett;[25] he waited 72 hours to be rescued, at a cost of $500,000.[9][39][40] The first attempt began in the Black Hills of South Dakota and ended in New Brunswick 1,800 miles (2,900 km) later. The second attempt, launched from Busch Stadium, cost $300,000 and lasted 9,600 miles (15,400 km) before being downed halfway in a tree in India; the trip set records at the time for duration and distance of flight (with Fossett doubling his own previous record) and was called Solo Spirit after Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis.[5][9] Fossett slept an average of two hours a night for the six-day journey, conducted in below-zero temperatures. After taking too much fuel to cross the Atlantic Ocean and circling Libya for 12 hours while officials decided whether or not to allow him into their airspace, Fossett did not have enough fuel to finish the flight. That year, Fossett flew farther for less money than better-financed expeditions (including one supported by Richard Branson) in part due to his ability to fly in an un-pressurized capsule, a result of his heavy physical training at high altitudes.[5] The Solo Spirit capsule was put on display at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum across from the Apollo 11 command module.[5]

After making an unscheduled landing in a plane, Fossett once walked 30 miles (48 km) for help.[8]

Scouting

Fossett earned the Eagle Scout award as a youth member of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), and in later years, he was described as a "legend" by fellow Scouts.[41] As a national BSA volunteer, he served as Chairman of the Northern Tier High Adventure Committee, Chairman of the Venturing Committee, member of the Philmont Ranch Committee, and member of the National Advisory Council. He later became a member of the BSA National Executive Board, and in 2007, Fossett succeeded Secretary of Defense Robert Gates as president of the National Eagle Scout Association. Fossett previously had served on the World Scout Committee.[3]

Fossett was honored with the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award in 1992. In 1999, he received the Silver Buffalo Award, BSA's highest recognition of service to youth.[6]

Awards and honors

In 2002, Fossett received aviation's highest award, the Gold Medal of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) and in July 2007, he was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame.[1] He was presented at the ceremony by Dick Rutan.

In 1997, Fossett was inducted into the Balloon and Airship Hall of Fame.[3] In February 2002, Fossett was named America's Rolex Yachtsman of the Year by the American Sailing Association at the New York Yacht Club.[13] He was the oldest recipient of the award in its 41-year history, and he was the only recipient to fly himself to the ceremony in his own plane.[13]

He received the Explorers Medal from the Explorers Club following his solo balloon circumnavigation. He was given the Diplôme de Montgolfier by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale in 1996. He received the Harmon Trophy, given annually "to the world's outstanding aviator and aeronaut", in 1998 and 2002. He received the Grande Médaille of the Aéro-Club de France, and the British Royal Aero Club's Gold Medal in 2002. He received the Order of Magellan and the French Republic's Médaille de l'Aéronautique in 2003.[3]

The Scaled Composites White Knight Two VMS Spirit of Steve Fossett,[42] was named in Fossett's honor by his friend Richard Branson, in 2007.[43][44] Following his disappearance, Peggy Fossett and Dick Rutan accepted the Spread Wings Award in Steve Fossett's behalf at the 2007 Spreading Wings Gala, Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum, Denver, Colorado.[45]

Death

Disappearance and search

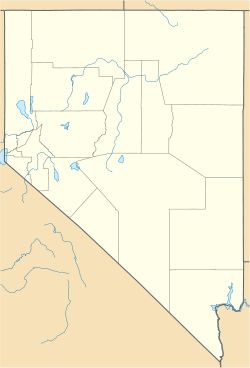

At 8:45 am, on Monday September 3, 2007 (Labor Day), Fossett took off in a single-engine Bellanca Super Decathlon airplane from a private airstrip known as Flying-M Ranch (), near Smith Valley, Nevada, 30 miles (48 km) south of Yerington, near Carson City and the California border.

The search for Fossett began about six hours later. The aircraft had tail number N240R registered to the "Flying M Hunting Club, Inc." There was no signal from the plane's emergency locator transmitter (ELT) designed to be automatically activated in the event of a crash, but it was of an older type notorious for failing to operate after a crash.[46] It was first thought that Fossett may have also been wearing a Swiss-made Breitling Emergency watch with a manually operated ELT that had a range of up to 90 miles (140 km), but no signal was received from it, and on September 13, Fossett's wife, Peggy, issued a statement clarifying that he owns such a watch, but was not wearing it when he took off for the Labor Day flight.[47][48]

Fossett took off with enough fuel for four to five hours of flight, according to Civil Air Patrol spokesperson Maj. Cynthia S. Ryan. [49] CAP searchers were told that Fossett had gone out for a short flight over favorite territory, possibly including the areas of Lucky Boy Pass and Walker Lake. At one point it was suggested that he might have been out scouting for potential sites to conduct a planned land speed run, but that later turned out to be untrue. A Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) spokesperson noted that Fossett apparently did not file a flight plan, and was not required to do so.[50] On the second day, Civil Air Patrol aircraft searched but found no trace of wreckage after initiating a complex and expanding search of what would later evolve into a nearly 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2) area of some of the most rugged terrain in North America. Noteworthy is the fact that Nevada is the most mountainous state in the U.S. and thus presented the highly experienced CAP searchers an extraordinary challenge from the standpoint of flying hundreds of hours in very difficult conditions safely. One the first day of CAP searching, operations were suspended by mid-day due to high winds, according to spokesperson and Public Information Officer, Maj. Cynthia S. Ryan, of the Civil Air Patrol. By the fourth day, the Civil Air Patrol was using fourteen aircraft in the search effort, including one equipped with the ARCHER system that could automatically scan detailed imaging for a given signature of the missing aircraft.[51] By September 10, search crews had found eight previously uncharted crash sites,[52][53] some of which are decades old,[54] but none related to Fossett's disappearance. The urgency of what was still regarded as a rescue mission meant that minimal immediate effort was made to identify the aircraft in the uncharted crash sites,[55] although some had speculated that one could have belonged to Charles Clifford Ogle, missing since 1964.[56] All told, about two dozen aircraft were involved in the massive search, operating primarily from the primary search base at Minden, Nevada, with a secondary search base located at Bishop, California. CAP searchers came from Wings across the United States, including Nevada, Utah, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Idaho, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Texas. [57]

On September 7, Google Inc. helped the search for the aviator through its connections to contractors that provide satellite imagery for its Google Earth software. Richard Branson, a British billionaire and friend of Fossett, said he and others were coordinating efforts with Google to see if any of the high-resolution images might include Fossett's aircraft.

On September 8, the first of a series of new high-resolution imagery from DigitalGlobe was made available via the Amazon Mechanical Turk beta website so that users could flag potential areas of interest for searching, in what is known as crowdsourcing. By September 11, up to 50,000 people had joined the effort, scrutinizing more than 300,000 278-foot-square squares of the imagery. Peter Cohen of Amazon believed that by September 11, the entire search area had been covered at least once. Amazon's search effort was shut down the week of October 29, without any measurable success.[58][59] Major Cynthia Ryan later said it had been more of a hindrance than a help. She said that persons purporting to have seen the aircraft on the Mechanical Turk or have special knowledge clogged her email during critical days of the search, and for even months afterward. Many of the ostensible sightings proved to be images of CAP aircraft flying search grids, or simply mistaken artifacts of old images. Psychics flooded the search base in Minden with predictions of where the aviator could be found. Ryan got the majority of these calls personally, often at her home, in the middle of the night. One man from Canada was particularly persistent with daily calls to Ryan, interfering with her press briefings. Ryan asked her Incident Commander to issue a cease and desist order, backed up by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) if necessary. Ryan noted that every message, letter, or phone call was taken seriously — which swamped the USAF specialists assigned the task of reviewing every one of them without regard to apparent plausibility. In retrospect, the crowdsource effort was "not ready for prime time," according to Major Ryan.

On September 12, survival experts speculated that Fossett was likely to be dead.[60][61]

On September 17, the Nevada Wing of the Civil Air Patrol said it was suspending all flights in connection with its search operations,[62] but National Guard search flights, private search flights and ground searches continued.[63]

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) began a preliminary investigation into the likely crash of the plane that Fossett was flying.[64] The preliminary report originally stated that Fossett was "presumed fatally injured and the aircraft substantially damaged", but was subsequently revised to remove that assumption.[65] Fossett's friend and fellow explorer, Sir Richard Branson, made similar public statements.[66]

On September 19, 2007, authorities confirmed they would stop actively looking for Fossett in the Nevada Desert, but would keep air crews on standby to fly to possible crash sites. "Nobody is giving up on this man", said department spokesman. "The search is going to continue. It's just going to be scaled back", he said.[67] On September 30, however, it was announced that after further analysis of radar data from the day of his disappearance, ground teams and two aircraft had resumed the search.[68]

On October 2, 2007, the Civil Air Patrol announced it had called off its search operation[69] Maj. Ryan later noted that the search was the largest, most complex peacetime search for an individual in U.S. history.

On August 23, 2008, almost a year after Fossett went missing, twenty-eight friends and admirers conducted a foot search based on new clues gathered by the team. That search concluded on September 10.[70][71]

Search and rescue costs

On May 1, 2008, the Las Vegas Review-Journal attributed to Nevada State Governor Jim Gibbons's spokesman, Ben Kieckhefer,[72] the Governor's decision to direct the state to charge the family of the late Steve Fossett for the $687,000 expense of the search for Fossett.[73] Kieckhefer later played that early report down, when he told the Tahoe Daily Tribune that Nevada did not intend to demand an involuntary payment from Fossett's widow, but that such a payment would be voluntary: "We are going to request that they help offset some of these expenses, considering the scope of the search, the overall cost as well as our ongoing budget difficulties."[74] Hotelier Barron Hilton, from whose ranch Fossett had departed on the day he went missing, had previously volunteered $200,000 to help pay for the search costs.[73][74]

In his later comments to the Tahoe Daily Tribune, Kieckhefer denied outright that a bill for the family was being prepared, and he said, "It will probably be in the form of a letter",[74] which Kieckhefer indicated would include a financial outline of the steps taken by the state, the associated costs, and a mention of the state's ongoing budget difficulties.[74]

Days prior to this announcement, state Emergency Management Director Frank Siracusa noted that "there is no precedent where government will go after people for costs just because they have money to pay for it. You get lost, and we look for you. It is a service your taxpayer dollars pay for",[73] although he conceded that legally any decision would rest with Gibbons. At an April 10, 2008 Legislature's Interim Finance Committee hearing, Siracusa indicated that he had hired an independent auditor to review costs incurred by the state in searching for Fossett, but added, "We are doing an audit but not because we are critical of anybody or suspect something was done wrong".[73][75] Chairman Morse Arberry queried Siracusa as to why, since they lacked funds, had the state not billed the Fossett family for its search costs, to which Siracusa did not directly respond.[73][75] In his later interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, he stated that his comments to the Committee may have given the false impression that he had hired an auditor for the purpose of later challenging the state's financial burden incurred on its behalf by the National Guard during the search operation.[73] Upon interview regarding reports that the state would seek payment, Arberry was recorded as stating that he was glad to hear steps were being taken to try to recoup some of the costs.[74]

The Nevada search cost $1.6 million, "the largest search and rescue effort ever conducted for a person within the U.S." Jim Gibbons asked Fossett's estate to shoulder $487,000 but it declined, saying Fossett's wife had already spent $1 million on private searching.[76]

Recovery of wreckage and remains

On September 29, 2008, a hiker found three crumpled identification cards in the Eastern Sierra Nevada mountain range in California about 80 miles (130 km) south-southeast of Fossett's take-off site. The items were confirmed as belonging to Fossett and included an FAA-issued card, his Soaring Society of America membership card and about ten $100 bills.[77][78]

On October 1, late in the day, air search teams spotted wreckage on the ground at coordinates at a height of 10,100 feet (3,100 m) and about 750 yards (690 m) from where the personal items had been found. Later that evening the teams confirmed identification of the tail number of Fossett's plane. The crash site is on a slope beneath the southwest side of a ridge line (600 feet (183 m) lower than the top of the ridge) in the Ansel Adams Wilderness and in Madera County, California. Other named places near the crash site include Emily Lake (0.7 miles (1.1 km) northeast), Minaret Lake (1.8 miles (2.9 km) west-southwest), the Minaret peaks (3 miles (5 km) west), Devils Postpile National Monument (4.5 miles (7.2 km) southeast) and the town of Mammoth Lakes (the nearest populated place, 9 miles (14 km) east-southeast). The site is 10 miles (16 km) east of Yosemite National Park.[79][80] A detailed map of the crash site can be found at Google Maps; the map description includes a link to a file for use with Google Earth.[81]

Over the next two days, ground searchers found four bone fragments that were about 2 inches (5 cm) by 1.5 inches (4 cm) in size. However, DNA tests subsequently showed that these fragments were not human.[79][82][83]

On October 29, search teams recovered two large human bones that they suspected might belong to Fossett. Tennis shoes with animal bite marks on them were also recovered. On November 3, California police coroners said that DNA testing of the two bones by a California Department of Justice forensics laboratory confirmed a match to Fossett's DNA. Madera County Sheriff John Anderson said Fossett would have died on impact in such a crash, and that it was not unusual for animals to drag remains away.[84] This fact does not explain how the ends of the aerobatic harness he was wearing could have come free from the 5-point cam-lock, considering that their release requires the cam-lock knob be twisted a quarter-turn. Manipulating the cam-lock could not have been accomplished by someone other than Fossett. According to interviews by the Discovery Channel (who provided a camera crew the day after his FAA ID and $1005 were found by a hiker) the one fact that disputes the official findings was the location of hardware that had been part of the pilot's harness. Pilots who knew him were interviewed by the Discovery Channel for a January 2009 documentary on the incident in which they expressed certainty that the harness could not have been released by any animal that may have moved his body. The reason for their opinion pertains to the mechanism (twisting) required to release the harness and the fact that no other hardware was attached. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this harness was in use or being worn at the time of the crash.

As of 2009, Fossett's remains have yet to be interred.

NTSB report and findings

On March 5, 2009, the NTSB issued its report and findings.[85] It states that Fossett crashed at an elevation of about 10,000 feet, 300 feet below the crest of the ridge he was trying to cross. The elevation of peaks in the area exceeded 13,000 feet. However, the density altitude in the area at the time and place of the crash was estimated to be 12,700 feet. The aircraft, a tandem two-seater, was almost 30 years old, and Fossett had approximately 40 hours in this type. The plane's operating manual states that at an altitude of 13,000 feet the rate of climb would be 300 feet per minute. The NTSB report states that "a meteorologist from Salinas, California provided a numerical simulation of the conditions in the accident area using the WRF-ARW (Advanced Research Weather Research and Forecasting) numerical model. At 0930 [the approximate time of the accident] the model displayed downdrafts in the accident area of approximately 300 feet per minute." There was no evidence of equipment failure, nor of any medical problem, and the incident will probably be attributed to pilot error. The NTSB investigation declared that strong winds had probably crashed Steve Fossett's plane.[86]

On July 9, 2009, the NTSB declared the probable cause of the crash as "the pilot’s inadvertent encounter with downdrafts that exceeded the climb capability of the airplane. Contributing to the accident were the downdrafts, high density altitude, and mountainous terrain." [87]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Wilson, Sam; agencies (2007-06-06). "Profile: Steve Fossett". London: Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/09/05/nfossettprofile104.xml. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ Hildebrand, Kurt (2007-09-04). "Searchers looking for world record holder Steve Fossett". The Record-Courier. http://www.recordcourier.com/article/20070904/NEWS/70904002. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 "Steve Fossett: Always "Scouting For New Adventures" Part 1". Airport Journals. October 2006. http://www.airportjournals.com/Display.cfm?varID=0610009. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "Search continues for aviation adventurer Steve Fossett". CNN. September 4, 2007. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/09/04/fossett.missing/index.html. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 "Pioneer In the Sky". Stanford Magazine. http://www.stanfordalumni.org/news/magazine/1997/mayjun/articles/fossett.html. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "EAGLE SCOUT AND BSA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEMBER SETS WORLD RECORD". Boy Scouts of America. 2002-07-03. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20071011200209/http://scouting.org/media/press/2002/020703/index.html. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ "NESA President Steve Fossett: A Tribute" National Eagle Scout Association, Eagletter Winter 2008

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Branson fears missing Fossett is injured". CNN. 2007-09-05. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/09/05/fossett.missing/. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Smith, Bill; Deere, Stephen (2007-09-05). "Steve Fossett's plane is missing". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2007-09-07. http://web.archive.org/web/20070907161003/http://www.stltoday.com/stltoday/news/stories.nsf/stlouiscitycounty/story/CDBB74A9E1D3BA3C8625734D000DDA68?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Halvorson, Todd (2007-09-04). "Aviator Fossett tries to break distance record". Florida Today (USA Today). http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2006-02-05-fossett-nonstop-flight_x.htm. Retrieved 2006-02-05.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Rescuers to Resume Search for Plane Carrying Aviation Adventurer Steve Fossett". Fox News. 2007-09-05. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,295714,00.html. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mihelich, Peggy (2007-09-04). "Adventure defines Steve Fossett". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2007/TECH/09/04/fossett.profile/index.html. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "Rich Roberts Reports". yachtracing.com. http://www.yachtracing.com/richroberts/fossett02.html. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ Fiorino, Frances (2007-09-06). "Advanced Recon System Aids Fossett Search". Aviation Week. http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story.jsp?id=news/Foss09067.xml&headline=Advanced%20Recon%20System%20Aids%20Fossett%20Search&channel=null. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ↑ "Fossett Sets Another World Record". Eagletter 32 (2): : 11. Fall 2006.

- ↑ "List of records established by 'Steve FOSSETT (USA)':". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/pilot.asp?from=ga&id=1372. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Aviation Adventurer Steve Fossett Missing". CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/09/04/national/main3231260.shtml?source=RSSattr=HOME_3231260. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ↑ "Students, Fossett present capsule to Smithsonian". The Record. St. Louis, MO. http://record.wustl.edu/2002/09-13-02/fossett.html. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Capsule, Balloon, / Bud Light Spirit of Freedom Capsule". Collections Database. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. http://collections.nasm.si.edu/code/emuseum.asp?quicksearch=A20030128000&newstyle=single. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "NOAA helps guide balloonist around the world". NOAA. http://www.research.noaa.gov/spotlite/archive/spot_fossett.html. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ↑ Fossett sets record for longest nonstop flight February 11, 2006

- ↑ "Fossett sets solo flight record" - BBC News article dated March 3, 2005

- ↑ "Fossett makes history" - CNN.com article dated March 4, 2005

- ↑ "Current Absolute General Aviation World Records". Records.fai.org. http://records.fai.org/general_aviation/absolute.asp. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Adventurer Steve Fossett No Stranger to Tall Odds". NPR. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14176484&ft=1&f=3. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ "National Air and Space Museum to Welcome Steve Fossett’s History-Making Airplane for Permanent Display at Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center". Press Room. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. 2006-05-19. http://www.nasm.si.edu/events/pressroom/releaseDetail.cfm?releaseID=153. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Di Freeze (November 2006). "Steve Fossett: Always “Scouting for New Adventures” Part 2". Airport Journals. US. http://www.airportjournals.com/Display.cfm?varID=0611030. Retrieved 2008-10-02. "I had permission to do a low pass over the airport, and then I came around, landed and taxied up to the door of the museum and gave it to them."

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Free Distance:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=420. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Distance over a triangular course:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=16. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Free out-and-return distance:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=391. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over a triangular course of 1500 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=96. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over a triangular course of 1250 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=95. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over a triangular course of 750 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=93. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over a triangular course of 500 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=92. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over an out-and-return course of 1000 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=410. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Speed over an out-and-return course of 1500 km:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=411. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "Gliding World Records: Sub-class DO (Open Class Gliders) Absolute altitude:". History of Aviation and Space World Records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. http://records.fai.org/gliding/history.asp?id1=DO&id2=1&id3=98. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ "1996 Ironman Triathlon World Championship". http://ironman.com/assets/files/results/worldchampionship/1996.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ "What did Steve Fossett do for us?". Knight-Ridder. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-120230678.html. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ↑ "Steve Fossett Breaks Ballooning World Record". CBS News. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-54087549.html. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ↑ Beadle, Nicholas (September 12, 2007). "Missing adventurer Steve Fossett has tenuous ties to area". Jackson Sun. http://www.jacksonsun.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070906/NEWS01/709060304/1002. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Branson, Richard (2007-10-10). "My Friend, Steve Fossett". Time. http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1670216,00.html. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Nizza, Mike (2007-10-11). "The Legend of Steve Fossett Takes Root". New York Times. http://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/10/11/the-legend-of-steve-fossett-takes-root/index.html?ex=1349841600&en=45eab0da4e07992c&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Burack, Ari (10 October 2007). "Sir Richard Branson...". San Francisco Sentinel. http://www.sanfranciscosentinel.com/?p=5903. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Rocky Mountain News: Missing aviator Steve Fossett honored at Wings Over Rockies by Tillie Fong, November 3, 2007. Retrieved 2008-2-16.

- ↑ Levin, Alan (2007-09-06). "Fossett search stresses need for new beacons". USA Today (Gannett). http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-09-05-fossett_N.htm?csp=34. Retrieved 2007-09-08. "The small plane piloted by Fossett, 63, was equipped with an older emergency beacon that is notorious for failing to operate after crashes, according to federal safety officials and the agencies that monitor the emergency beacons."

- ↑ Geis, Sonya (2007-09-06). "Rescue Crews Find No Sign Of Missing Adventurer". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/05/AR2007090502116.html. Retrieved 2007-09-08. "In a telephone interview, [Fossett's friend Granger] Whitelaw said Fossett always wears a Swiss-made Breitling watch with the same type of electronic location transmitter that commercial jets use to alert rescuers when they crash."

- ↑ "Search for Fossett could solve decades-old mysteries". CNN. 2007-09-13. http://edition.cnn.com/2007/US/09/13/fossett/index.html?iref=mpstoryview. Retrieved 2007-09-13. "Fossett's wife, Peggy, issued a statement Thursday in response to questions about whether her husband was wearing a watch with an emergency transmitter on his flight. She said he owned such a Breitling watch but did not bring it on the trip."

- ↑ "Aviation record-holder Steve Fossett missing". CNN. 2007-09-04. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/09/04/fossett.missing/index.html. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Sonner, Scott (2007-09-04). "FAA: Adventurer Fossett's Plane Missing". Associated Press. http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=D8REQ4EG0&show_article=1. Retrieved 2007-09-04. and "Steve Fossett reported missing by US aviation authorities". The Guardian (London). 2007-09-04. http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,,2162338,00.html?gusrc=rss&feed=networkfront. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Fiorino, Frances (2007-09). "Advanced Recon System Aids Fossett Search". Aviation Week. McGraw-Hill. http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story.jsp?id=news/Foss09067.xml&headline=Advanced%20Recon%20System%20Aids%20Fossett%20Search&channel=null. Retrieved 2007-09-08. "According to CAP, a set of parameters describing the intended target, including its color and shape, is programmed into the ARCHER system."

- ↑ Friess, Steve (2007-09-10). "Search for Fossett turns up wrecks of 8 other small planes". San Francisco Chronicle (Hearst Communications Inc.): pp. A–1. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2007/09/10/MNF0S2BJT.DTL. Retrieved 2007-09-10. "The search for Fossett across a 17,000-square-mile (44,000 km2) swath of the Sierra Nevada has revealed the wreckage of eight other small planes..."

- ↑ "Searchers frustrated over Fossett search". USA Today. Associated Press. 2007-09-10. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-09-10-fossett_N.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-14. "...search parties have spotted wreckage of eight other airplanes that had been lost for years in and around the rugged mountains of western Nevada."

- ↑ Riley, Brendan (2007-09-08). "Vast, desolate area hinders Fossett search". Monterey Herald. http://www.montereyherald.com/ci_6836636. Retrieved 2007-09-10. "...another downed plane Friday that was spotted on a hillside about 45 miles (72 km) southeast of Reno...turned out to be an old crash, a plane last registered in Oregon in 1975"

- ↑ Steve Friess (September 10, 2007). "Search for Fossett turns up wrecks of 8 other small planes". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/09/10/MNF0S2BJT.DTL. Retrieved 2009-06-24. "...Little is known about the eight crashes spotted in the past week, because searchers "put boots on the ground" only long enough to ascertain they were not Fossett's plane, said Civil Air Patrol spokeswoman Maj. Cynthia Ryan."

- ↑ Gerdner, Tom (2007-09-08). "Aviator's Fate Puzzles Search Crews". Associated Press. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5h4Tt3Ok0yMNfSsatpddlmScxyEiQ. Retrieved 2007-09-08. "In their quest to find missing aviator Steve Fossett, searchers have come across eight uncharted plane crash wreckage sites. But none of the wrecks shed light on what may have happened to the multimillionaire."

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/09/08/fossett.ap/index.html

- ↑ 50,000 Volunteers Join Distributed Search For Steve Fossett, Wired News, By Steve Friess, September 11, 2007, 2:00 p.m.

- ↑ Online Fossett Searchers Ask, Was It Worth It?, Wired.com, Steve Friess, 11/6/2007 5:00 PM

- ↑ http://edition.cnn.com/2007/US/09/12/fossett.search.ap/index.html

- ↑ "Steve Fossett likely dead, survival experts say", http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20732023/

- ↑ "Missing - Steve Fossett". Check-Six.com. http://www.check-six.com/lib/Famous_Missing/Fossett.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/09/18/fossett.search.ap/index.html.

- ↑ "NTSB Preliminary Report - SEA07FAMS2 - on the loss of N240R". Ntsb.gov. http://www.ntsb.gov/ntsb/brief.asp?ev_id=20070917X01399&key=1. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ Howard, Scott and Stewart Campbell (2007-09-20). "Federal Agency Retracts Fossett Statement After KOLO 8 Probe". KOLO-TV News. http://www.kolotv.com/home/headlines/9904426.html. Retrieved 2007-09-21. "...the National Transportation Safety Board's officials preliminary report noted that Fossett was "presumed fatally injured and the aircraft substantially damaged.""

- ↑ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20071015/ap_on_re_us/steve_fossett

- ↑ Search For Missing Adventurer Wound Down |Sky News|World News

- ↑ "Search for Missing Aviator Steve Fossett Ramped Up After New Air Force Analysis - Local News | News Articles | National News | US News". FOXNews.com. 2007-09-30. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,298646,00.html. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ CNN (2007-10-03). "Search called off for adventurous aviator Steve Fossett". CNN News. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/10/02/missing.millionaire/index.html. Retrieved 2007-10-03. "The Civil Air Patrol has called off the search for multimillionaire adventurer Steve Fossett, nearly a month after he took off from a Nevada ranch, the agency announced Tuesday."

- ↑ "New search starts for Steve Fossett". Reno Gazette Journal. 2008-08-31. http://news.rgj.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080831/NEWS18/80831007. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ "Another Fossett search winding up in Nevada". US: Ksdk.com. 2008-09-10. http://www.ksdk.com/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=154490. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Office of the Governor, Nevada State (2008-03-12). "Governor appoints ben kieckhefer press secretary". Press release. http://gov.state.nv.us/PressReleases/2008/2008-03-12BenKieckhefer-PS.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 73.4 73.5 Vogel, Ed (2008-05-01). "MISSING ADVENTURER: Gibbons to bill Fossett widow". Las Vegas Review-Journal. http://www.lvrj.com/news/18443319.html. "Government's cost to hunt for multimillionaire was $687,000"

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 Chereb, Sandra (2008-05-01). "Nevada governor to ask Fossett widow for search money". Associated Press Writer (Tahoe Daily Tribune). http://www.tahoedailytribune.com/article/20080501/NEWS01/925589792. "Kieckhefer said any assistance from the Fossett family would be voluntary."

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "Agendas and Minutes". Interim Finance Committee (NRS 218.6825). Nevada Legislature. 2008-04-10. https://www.leg.state.nv.us/74th/Interim/Scheduler/committeeIndex.cfm?ID=10091.

- ↑ "Audit critical of Nevada search for Steve Fossett". Arizona Daily Star. June 26, 2008. http://www.azstarnet.com/sn/printDS/245620. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Kevin Fagan (2008-10-02). "Fossett items found near Mammoth Lakes". SFGate (San Francisco, California: Hearst Communications). http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/10/01/MNPT139M9N.DTL. Retrieved 2008-10-02. "(The cards) both are authentic, and both have been confirmed that they do in fact belong to Steve Fossett"

- ↑ The Press Association (2008-10-02). "Timeline: Steve Fossett disappearance". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media Limited). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/oct/02/usa2. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "Bones found near Fossett's plane". BBC News. 2008-10-31. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7701300.stm. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "Adventurer Fossett's plane, human remains found". Leader-Telegram. Associated Press (Eau Claire, Wisconsin: Leader-Telegram). 2008-10-02. http://www.leadertelegram.com/story-news.asp?id=BHUJ3SRVFS1. Retrieved 2008-11-04. ""It was a hard-impact crash, and he would've died instantly", said Jeff Page, emergency management coordinator for Lyon County, Nev., who assisted in the search."

- ↑ Map data provided by the Madera County Sheriff's office.

- ↑ Jesse McKinley (2008-10-02). "Remains Are Found at Site of Fossett Plane Crash". NYTimes.com (New York, New York: The New York Times Company). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/03/us/03fossett.html. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ Jia-Rui Chong (2008-10-04). "Wreckage of Steve Fossett's plane is airlifted from crash site". latimes.com (Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles Times). http://www.latimes.com/news/printedition/california/la-me-fossett4-2008oct04,0,5421336.story. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ "Bones confirm Steve Fossett death". BBC News. 2008-11-03. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7707397.stm. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ↑ "NTSB Report". Ntsb.gov. http://ntsb.gov/ntsb/brief2.asp?ev_id=20081007X17184&ntsbno=SEA07FA277&akey=1. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ "Investigators: Strong winds probable cause of Fossett crash". CNN.com. 2009-07-09. http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/07/09/fossett.crash.cause/index.html. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ↑ ""Factual Report - Aviation"". National Transportation Safety Board. http://www.ntsb.gov/ntsb/GenPDF.asp?id=SEA07FA277&rpt=fa. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

Further reading

- Fossett, Steve; Hasley, Will (2006). Chasing the Wind: The Autobiography of Steve Fossett. Virgin Books. ISBN 9781852272340.

External links

- Official website

- Timeline: Steve Fossett

- In pictures: Steve Fossett

- BBC, Profile: Steve Fossett

- "FAI Awards received by Steve FOSSETT (USA)". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). http://www.fai.org/awards/recipient.asp?id=2008. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- "List of records established by 'Steve FOSSETT (USA)'". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). http://records.fai.org/data?p=1372. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- Obituary from The Economist, February 21, 2008

- New attempts by adventure athletes to search territory previous searches could not cover

- Weather radar loop for September 3, 2007 around Fresno, California, including the crash site.

|

||||||||||||||